Two of the most recognizable aspects of warmer months will be the brightly coloured blossoms and aromatic scent of honeysuckle in the atmosphere. Although invasive species can be thought of a garden nuisance, honeysuckle is often employed as an addition to a cover for fences and walls. As either a vine or a tree, honeysuckle is a robust, colorful addition to any yard or garden.

Description

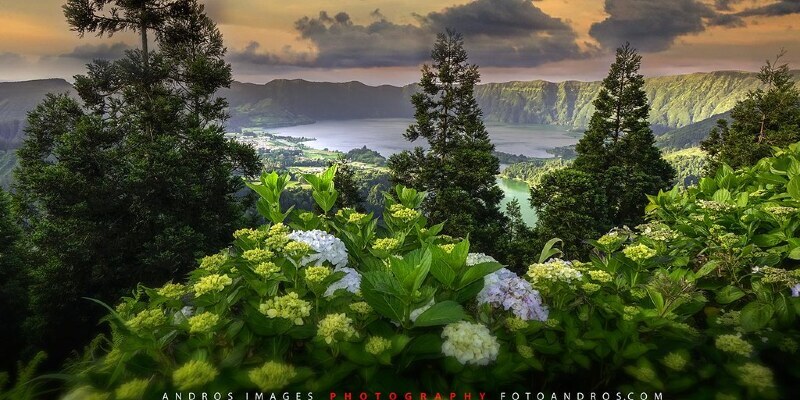

Honeysuckle is the general, common name for about 200 species of deciduous, semi-evergreen flowering vines and shrubs. Even though honeysuckle often grows throughout Europe, Asia and various parts of the Americas, there are an estimated 100 species located in China alone. In addition to creating sweet-smelling, trumpet-shaped blossoms which range in color from white to yellow to bright orange, pink and red, honeysuckle plants also produce black, red or blue berries. Even though the nectar in the base of honeysuckle flowers can be absorbed, the berries are toxic and should not be eaten.

Forms

Sometimes referred to as woodbine and goat’s leaf, fragrant honeysuckle’s numerous species are proven to attract bees, birds and other wildlife. Two of the most widely recognized species of honeysuckle include Lonicera periclymenum, better called common honeysuckle, and Lonicera japonica, known as Japanese Honeysuckle. Common honeysuckle, typically found in Europe, can be known to climb up to 32 feet high, has white and yellow colored blooms and bananas red berries. Japanese Honeysuckle produces a vanilla scent and could possibly grow to over 80 feet. It also possesses double-tongued white flowers which turn yellow as they mature. Japanese Honeysuckle is also referred to as an invasive species and may be classified as a weed.

Maintenance & Care

Honeysuckle vines and shrubs often grow wild, but can be trained to develop a trellis or within a garden as groundcover. Even though honeysuckle is a hardy, low maintenance plant, it thrives in moist dirt. In summer months, watering and mulching is vital to preserving the roots and also discouraging aphids from attacking the plant. Many honeysuckle species grow well in full sunlight, but can also tolerate partial shade. While some varieties need some polishing during the winter season, most do not have to be pruned.

Fun Facts

In addition to being used as a cut flower in bouquets, baskets and potpourri, honeysuckle has long been related to superstition. Throughout the Victorian age in Great Britain, honeysuckle flowers were often grown in gardens and around the doorways of homes to ward off witches and evil spirits. It was also considered to cause fine dreams and enhance mood when put under a pillow. Now, honeysuckle is often utilised in herbal and aromatherapy pillows. Honeysuckle, sometimes referred to as woodbine, has also been often mentioned in classic British literature. The two William Shakespeare and Geoffrey Chaucer refer to this honeysuckle plant at “Twelfth Night,” “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” and “The Canterbury Tales.”